The term circular is reused so often these days that it is almost impossible to call it circular. It seems to be subject to the same inflation as the concept of sustainability. Therefore an answer to the question: what is really circular?

An example. An advertisement shows images of a new kind of garden chair. The voice in the advertisement speaks of a circular garden chair. Because, although the product is oil-based (because plastic), the garden chair is reusable. Admittedly not as a garden chair, but as a roofing material. Can we speak of circular here?

The definition of circularity is the system in which raw materials are continuously reused and conserved, without waste production.

Okay, the raw material of the garden chair from the example can be reused. In fact, it can become roofing material. But that is not with value retention. So it cannot be continuous. Roofing does not become a garden chair again so quickly.

Moreover, the processing of the garden chair appears to release waste. For example, the stream of metal from the screws and springs, and the rubber from under the legs. These have not found a new cycle, and thus can be labeled as waste. Then there is also the dependence on user and recycling market to realize the potential recycling. If the garden chair ends up in the residual waste or the recycling industry cannot find a market for the recyclate, the (semi)circular party will not continue.

Conclusion: this garden chair is not circular. It is (low-value) recyclable, though.

Two models for waste management and circularity

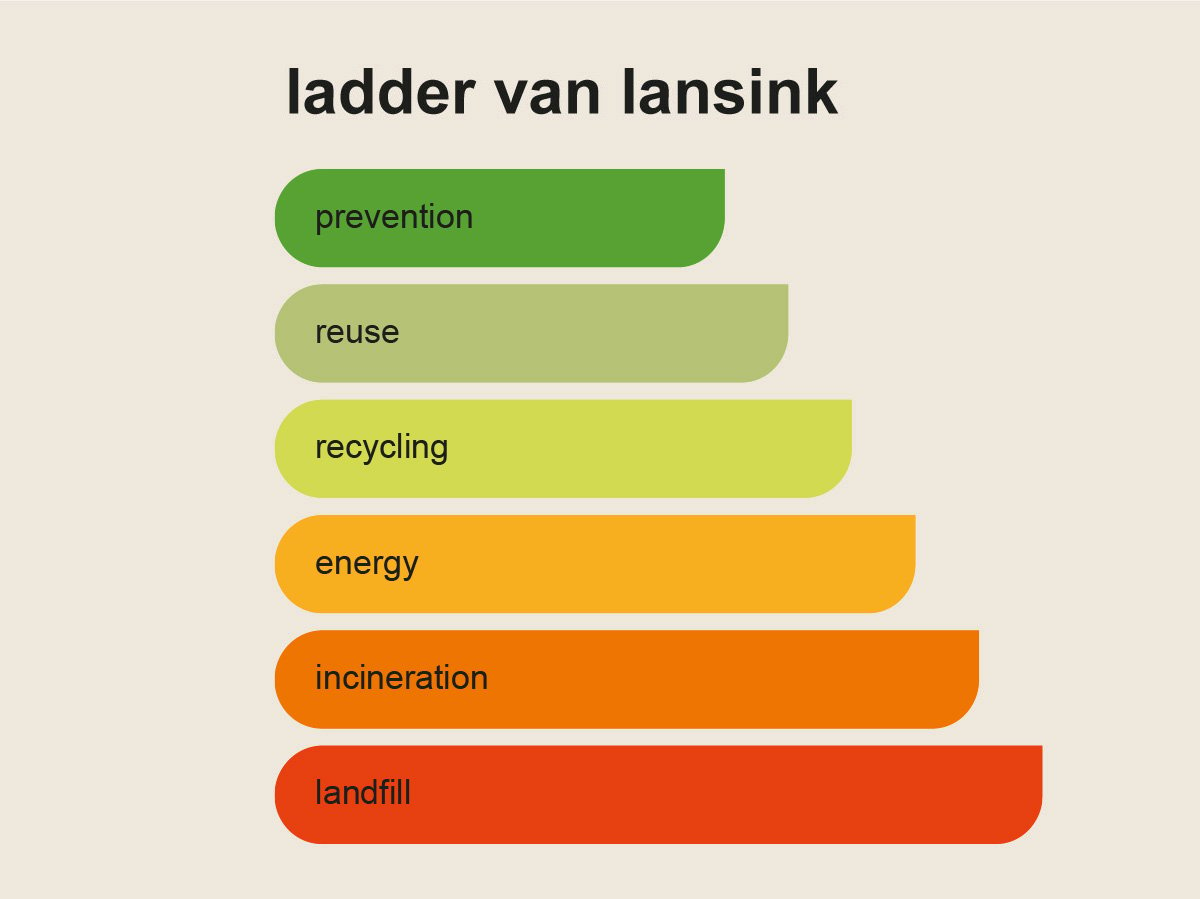

There are two widely used models by which the degree of circularity of a product can be demonstrated. The first (and the oldest, dating as far back as 1979) is Lansink's Ladder, named after its creator, a second chamber member of yore. This ladder has six steps. At the highest (prevention), no more garden chair is made at all. The second (reuse) comes closest to circular. And the third step is about recycling, actually what happens to the garden chair. The other steps are completely taboo in the circular economy. Using raw materials to generate energy, burning and landfilling.

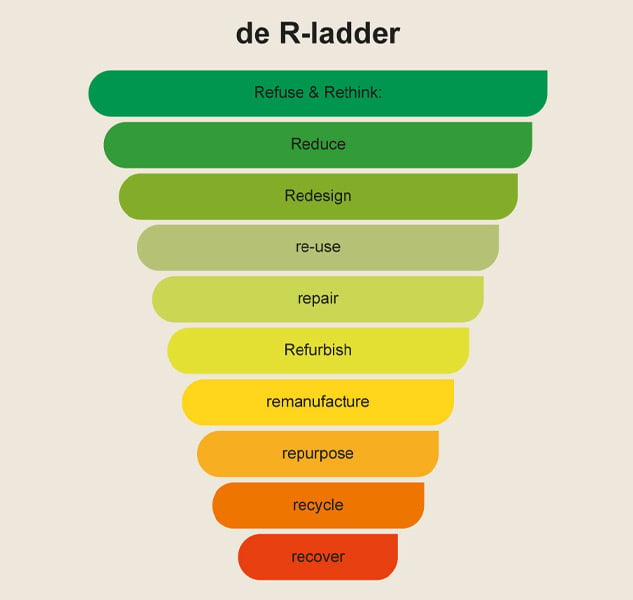

More specific to the circular economy is the much later developed R ladder. This ladder shows different strategies for circularity. The higher up the R-ladder, the lower the resource use. With the highest step being the renunciation of production. And below that, descending each time, a circular strategy of reusing, repairing, refurbishing, overhauling and recycling.

Question is: what has to happen to the garden chair for it to be labeled circular? Two things. And actually three. Or even four, if you think even further.

1: Continuous reuse

First: the garden chair should be able to become a garden chair again after it has reached the end of its life. And again, and again, and again. Only then can raw materials be continuously reused and preserved. There are several ways to do that. The regular way of recycling, mechanically, makes the garden chair's raw material suitable for lower-value uses. But new ways of recycling are under development that allow the garden chair to be broken down completely down to the molecule and become raw material again with which anything can be made: chemical recycling. In addition, the chair can be designed in such a way that it is continuously reusable at the material and component level.

By the way, garden chairs do not quickly reach the end of their lifespan, they do reach the end of the user's taste. Or at the end of fashion. With repair and maintenance, a garden chair remains in the owner's taste much longer.

2: A resource that does not become waste

Second, ensure that the garden chair does not produce waste when reused. The metal flows, the rubber caps under the legs; these flows must all be brought into circulation to speak of a circular product. Milgro has an extensive network of different cycles and can help companies bring a waste stream into one of the value chains that are being built up for this purpose, all over the country. In this way, a waste stream is no longer waste. Milgro has several examples of how this is done, for example, for material from label carriers, or for phosphates or wastewater. And so I'm sure the screws and other metal parts of the garden chair can also find a new value chain to circle around infinitely.

3: Waste is nutrition

There was also a third way? Yes, the true circular purists believe that circularity should only be talked about when raw materials can also be reabsorbed into nature. Waste is food for mother earth. The leaves that fall from the trees are absorbed into the earth and provide nutrition for the tree to continue growing. The question is whether a plastic garden chair, with petroleum as its base, forever extracted from the earth, can be labeled circular according to this premise.

4: Forget the garden chair

And the fourth? Forget the garden chair. The advertising for the garden chair is superfluous; so is the garden chair itself. It does not need to be produced at all. It is the epitome of circularity, the highest rung on both ladders. Just lie back in the tender grass.

Stay informed

Stay up to date on all new developments? Follow us on LinkedIn or Instagram. Or subscribe to the newsletter. Are you curious about what Milgro can do for your operations and waste process? Contact us